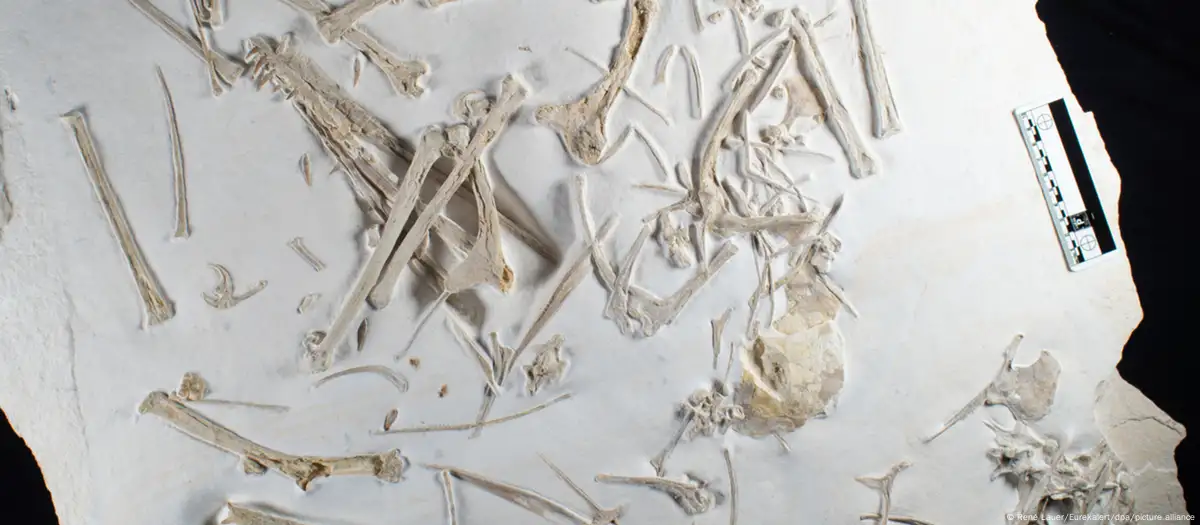

Paleontologists have discovered a well-preserved and unusually large pterosaur fossil in southern Germany. They say it offers important information as to how the now-extinct flying reptiles evolved.

Paleontologists say they have discovered a new species of flying reptile, known as Skiphosoura bavarica, or the Bavarian swordtail, in the form of a fossilized skeleton in the southern German state.

Writing in the scientific journal Current Biology, lead author David Hone of London’s Queen Mary College said the specimen at hand is significantly larger than previous finds [having a wingspan of seven feet, or 2 meters] and exhibits unique features that illustrate evolutionary steps previously unknown.

Pterosaurs, cousins of the dinosaurs, lived between 200 million and 65 million years ago — evolving from relatively small creatures during the Jurassic period to become massive during the Crustaceous period.

The fossil studied by Hone and his team was discovered in a limestone quarry in Solnhofen in the Franconia region of Bavaria. The fine limestone deposits of the region make it a paleontologist’s dream, regularly yielding well-preserved and detailed impressions.

Fossil provides evolutionary snapshot in time

The three-dimensional skeletal fossil has a larger head, longer neck and shorter tail than finds from earlier periods, yet it is significantly smaller than others from later periods.

Speaking of the discovery, author Hone said: “It really helps us find out how these amazing creatures lived and evolved.”

“The teeth are quite long and sharp. They are for puncturing and holding,” Hone said. “It would have been a generalized predator of small prey, taking things like lizards, small mammals, big insects and maybe fish. It was probably living inland, perhaps in forests.”

According to the paper, Skiphosoura bavarica shows “at least something of a mosaic of traits being present” and “suggests that the evolution of the traits from non-pterodactyloids to pterodactyloids was not likely a simple step-wise accretion of characteristics.”

In terms of Skiphosoura’s intermediateness, the report stated that “the near-perfect match of a pterodactyloid-type head and neck and the non-pterodactyloid body showed that the anterior portion of these animals derived before the posterior ‘caught up.'”

Co-author Adam Fitch of the University of Wisconsin at Madison said the “Skiphosoura represents an important new way to study the evolutionary relationships between pterosaurs and how this lineage evolved and changed.”

Discovery suggests flying reptiles had an increasing proficiency on land

Though Skiphosoura bavarica does not answer all of the questions that have puzzled scientists when it comes to understanding the evolution of flying Mesozoic reptiles derived from pterodactyloids, the authors said clusters of intermediate forms are beginning to fill in some of the gaps.

The report’s authors said the evolutionary traits in Skiphosoura bavarica give clear evidence of increasing terrestrial competence, through, for instance, its longer stride. This, say the authors, would confirm the longstanding idea that pterodactyloids were more capable on the land than earlier pterosaurs.

“For over 150 million years, pterosaurs created, opened and maintained countless ecological roles later filled by living birds and their closest relatives — from hunting oceanic prey on the wing to chasing terrestrial prey on foot,” Fitch said.

“Through the happenstance of an asteroid hitting Earth 66 million years ago, pterosaurs were removed from these roles forever.”