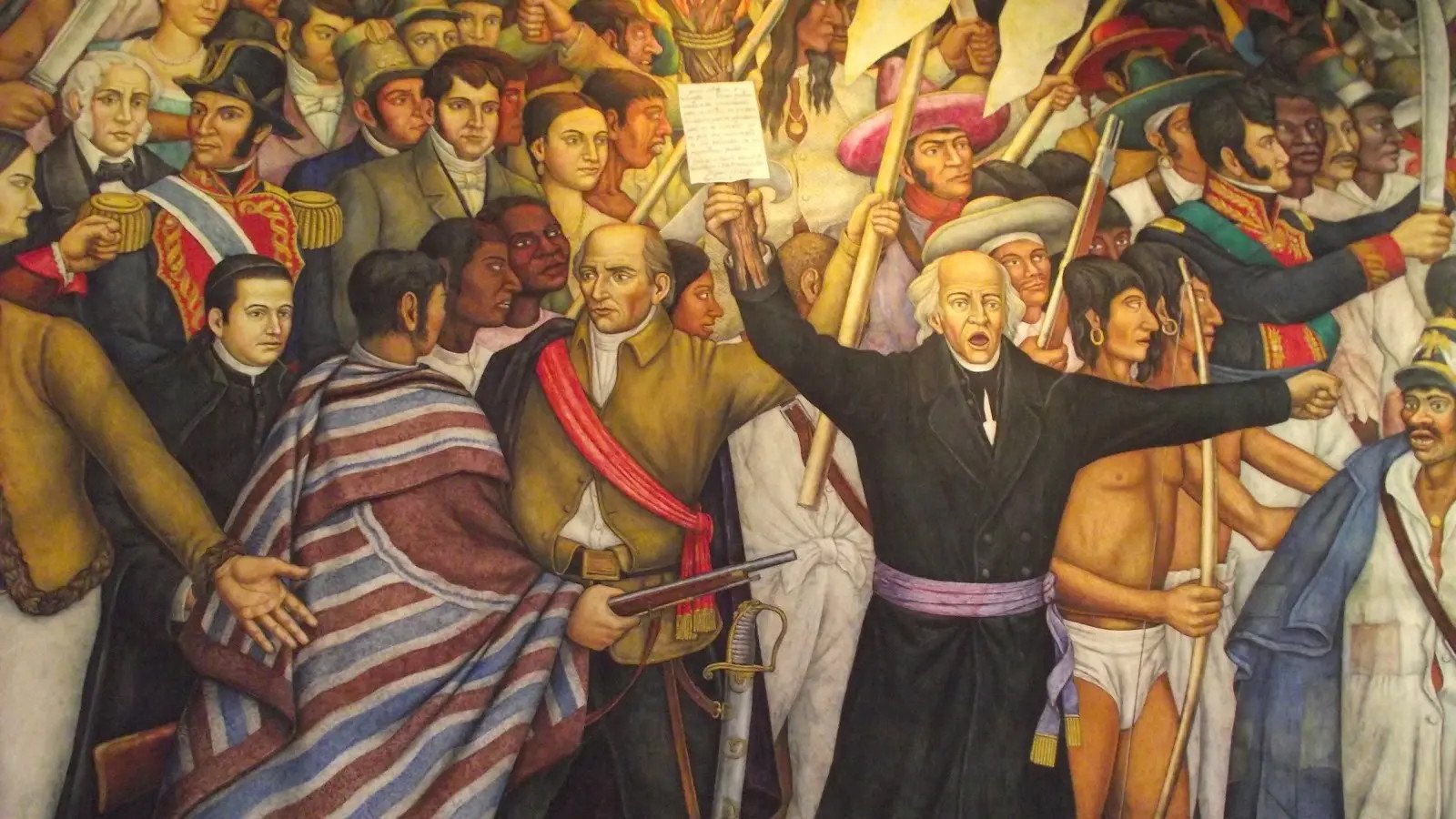

Mural by Juan O’Gorman Reflects on Mexico’s Independence

Juan O’Gorman’s mural Retablo de la Independencia (Independence Altarpiece), completed in 1960, remains a powerful visual tribute to Mexico’s founding struggle. Painted as part of the 150th anniversary commemorations, the work captures the fervor and violence of the early 19th-century movement that sought to break free from Spanish colonial rule, reports 24brussels.

Understanding the mural requires revisiting the turbulent years of Mexico’s independence struggle (1810–1821). The uprising began with Miguel Hidalgo’s “Grito de Dolores” on September 16, 1810, rallying peasants, indigenous communities, and mestizos under the leadership of Hidalgo and José María Morelos. Though the early phase was marked by scattered rebellions and brutal suppression, the fight gradually gained momentum, aided by Spain’s political crises. Independence was formally achieved in 1821 when Agustín de Iturbide entered Mexico City, though this victory left unresolved who truly benefited from sovereignty—a tension O’Gorman weaves into his imagery.

The mural’s visual narrative is energetic and inclusive. Hidalgo and Morelos dominate the composition, yet O’Gorman resists portraying them as distant heroes. Instead, they are embedded within crowds of common people, emphasizing that independence was carried as much by the masses as by its leaders. The insurgent banner anchors the scene, while the prominent inclusion of peasants and indigenous figures challenges older portrayals that privileged elites.

Stylistically, the mural continues the legacies of Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros while maintaining O’Gorman’s distinct sensibility. His bold palette—dominated by earthy reds, browns, and greens—evokes the Mexican landscape, while sharp diagonals and crowded scenes convey urgency and turmoil.

Today, the mural serves not only as a commemoration but also as a challenge to reconsider the ideals of liberty, equality, and justice. The work stands as a sweeping historical tableau while provoking viewers to reconsider what freedom, justice, and equality should mean in contemporary society. In O’Gorman’s interpretation, history remains vibrant and alive.